Mainlining Nostalgia: Making the Winamp Skin Museum

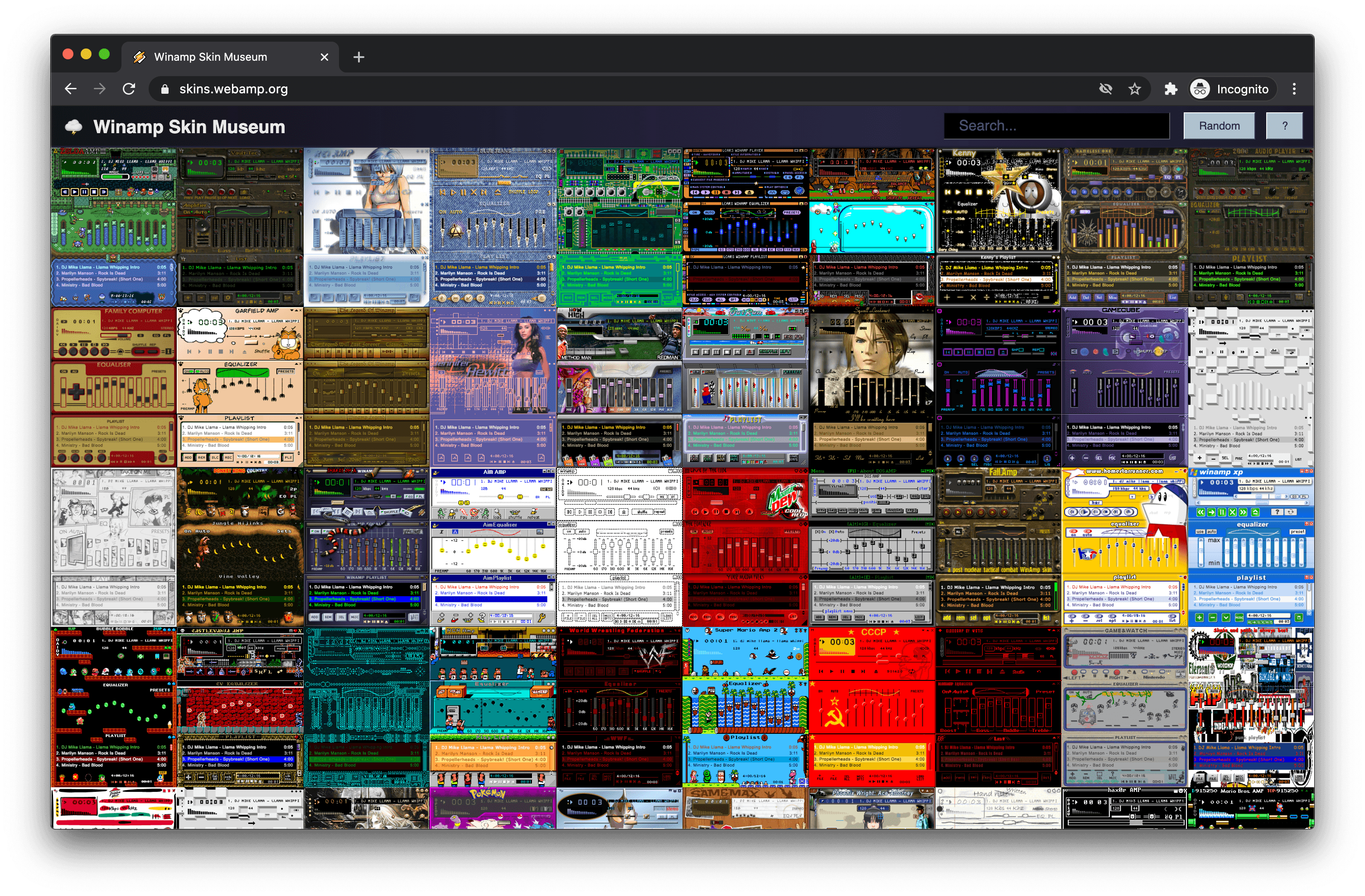

Early this month I published a project that I’ve been tinkering with, on and off, for more than two years. It’s a website where you can endlessly scroll through Winamp skins. It features instant search and live preview. You can find it here: skins.webamp.org.

The project has proven more successful than I could have hoped, serving ~30 million screenshots to ~50,000 users in the first 24 hours and receiving coverage by PC Gamer, AV Club, Gizmodo, The Verge, Hacker News, and Reddit in the following days. So I thought I'd share some of the thinking that went into the design and execution, which I believe contributed to its success.

Performance is a Feature #

I hope that the site feels simple to users, even obvious. At its core it’s just a single scrollable grid of filterable screenshots with a live preview when you select one. But, both the decision behind that design, and how I built it, were driven by a well defined vision.

Websites that curate skins have been around since skins were first “a thing”. However, since that time, the web, bandwidth, and CPUs have come a long way. So, I set out to build a website that leveraged this technical progress to saturate the user with as much Winamp skin aesthetic as possible. Delivering on this vision required solving two interesting problems:

Get lots of skins with screenshots

Build an interface that maximizes the skins we can show across all possible axes

Finally I had an additional constraint. I, correctly as it turns out, suspected that a site like this might generate a lot of interest, so I needed to ensure that the site could withstand large traffic spikes, and that the cost of running the site would be reasonable even in the face of large spikes.

In the rest of the post I’ll outline how I solved these problems.

Get Lots of Content #

This was the easy part. I had already worked with the Internet Archive to collect many Winamp skins. The attention this generated resulted in more people with skins coming forward. This grew the collection up to its current size of ~65,000 skins. That’s more than enough to saturate any user!

As part of this collaboration, I had also written some code that used browser automation together with my browser clone of Winamp — Webamp — to automatically generate screenshots of all 65k skins.

Design to Maximize Image Density #

With a large number of skin screenshots in hand, the next step was to come up with a design that could show the user as many of them as possible.

From a screen real estate perspective this was easy: just show wall-to-wall skins. I also scaled them down by half so that more could fit on the screen while still leaving them recognizable. This works particularly well on high density displays where sub-pixel rendering means we are still showing all the pixels.

From an interaction perspective, maximizing density meant making it as easy as possible for users to get more skins. Infinite scroll is the canonical answer to this, so it’s what I did.

So, we are left with an interface that is just an infinite scroll of a wall-to-wall grid of skin images.

Sort the Best Ones First #

After maximizing the number of skins we can show the user — both in space and time — how else can we increase the density? By having more Winamp essence in each screenshot. By that, I mean delivering the most evocative images possible. But how do we know which skins are the most interesting?

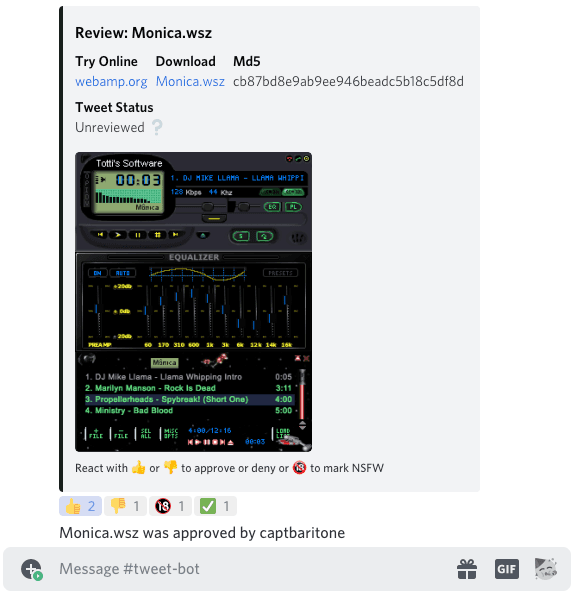

After collaborating with the Internet Archive, I built a Twitter bot @winampskins that tweets out a few Winamp skins a day. To ensure a consistent quality level from the bot, I built a separate chat bot in our Webamp Discord channel. This bot can be prompted via a !review command to show a random Winamp skin from the Internet Archive collection. People in the chat can then react to that message with a 👍 or 👎 to approve/reject the skin for inclusion in the Twitter bot’s queue.

This gave us a binary good/bad rating for a large number of skins, but after each skin was tweeted, I gained even more data. The number of likes that a skin’s tweet received could act as a proxy for how well that skin resonated with a modern audience. So, I scraped the “like” count for each of the tweeted skins and used that as the sorting criteria for the list.

Ideally that would be the end of our work, but there was one more wrinkle. It turns out there are a shocking number of Winamp skins that are… pornographic. These stand out in the grid and are not something I wanted to show people without their consent.

I was able to run the generated screenshots through NSFW.js, a machine learning model trained to detect pornography. The results that NSFW.js generated tuned out pretty hit or miss, so I paired it with a manual process. I augmented our Discord bot (mentioned above) and gave it a mode where it would prompt the user with skins that NSFW.js thought were likely to be, well… NSFW, and let a real person make the call in chat via an emoji “reaction”. In this way we were able to review many of the most egregious examples pretty quickly.

Finally, I added a “Report NSFW” button to each skin in the Museum which causes our Discord bot to prompt us to review the skin.

Make it Fast and Cheap #

We’ve maximized density on the layout, interaction, and quality fronts. What else can we do to increase saturation? Optimize for performance! The faster we can get the screenshots to user, the more they’ll be able to see while they are on the site.

How can we engineer the site to deliver content as fast as possible while still keeping the site cheap to run?

For hosting the HTML and JavaScript, I selected Netlify which is a host optimized for static sites. They feature a GitHub integration which automatically builds and deploys a new version of the site every time you push to GitHub. Unlike traditional web hosts where your files live on one server, Netlify takes advantage of the fact that site is static and distributes the site across their Content Delivery Network (CDN). This means that when a user requests the content, it is returned from a server that is geographically nearby, which can dramatically improve page speed. Best of all, they offer a free tier for side projects!

The next challenge was to give the appearance of a single grid of skins without loading 65k images all at once. To do this I used a classic technique called “windowing” where we render a huge empty <div /> as tall as the real grid would be, and then only populate it with <img /> tags in relatively small part of the grid that the user is currently scrolled to.

That still leaves a lot of images to load. How can we make that fast?

First we want the images to be a small as possible. Luckily there are many open source tools to optimize images for size. I ran all the 65k screenshots through imagemin.

The next step is to get them to the user quickly. Lucky for me CloudFlare offers a free CDN caching service for non-business projects like this. With CloudFlare all the requests for images and skins go through their CDN so they can serve the images from their geographically local servers where possible. This proved crucial since the site ended up handling ~30 million static resource requests in the first 24 hours!

An additional UX detail I added was having each image fade in only after it is fully loaded. By default browsers will reveal images top to bottom as they load, so a large grid of images loading at the same time can become quite chaotic. This small animation detail makes the loading experience much calmer.

Finally we are left with search. With a corpus this big, users need some mechanism other than scrolling to find what they are looking for. Lucky for me, Algolia offers a free tier of their shockingly fast search-as-a-service. I scraped as much text content (readme files, filenames, etc) out of each skin as I could, and uploaded it to Algolia. I also uploaded some additional metadata about each skin so that when a user types in the search bar, Algolia’s API actually returns enough data to request the matching images immediately.

Conclusion #

I believe that the Winamp Skin Museum owes its initial success to the vision of maximizing the quantity and quality of content we can show, and then using both design and performance-orienting engineering to realize that vision.

If this type of project sounds interesting to you, but you lack content, I’d urge you to take a look at the Internet Archive’s collections. They have troves of artifacts, any of which would be worth honoring with a purpose-built website.

Thanks to António Afonso for suggesting I write this post.

If you'd like to hear more, I gave a talk entitled Design as an Optimization Problem in which I expanded upon some of the ideas in this post.