I think my new paste bin should be immune to takedown notices

I recently released a new website called HashBin. It takes advantage of some unique properties of the hash portion of a URL to avoid ever being able to see the content the pastes it helps create.

What is the "hash" of a URL, and why is it special? The hash is the portion of

the URL that follows the # symbol. For example:

http://example.com#the-hash

Here's what makes it special:

When an agent (such as a Web browser) requests a web resource from a Web server, the agent sends the URI to the server, but does not send the [hash].

-- Wikipedia

At first glance that may not seem terribly note-worthy, but it allows for something very interesting. It allows you to store information in a URL that the server never sees, but can be read by JavaScript.

You can think about it like this, a URL contains two distinct pieces of information:

A pointer to a location where it can download a web app

A piece of data which you want that app to interpret

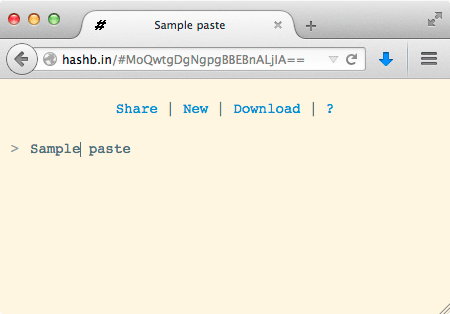

This is exactly what I have built. When your browser requests http://hashb.in

it retrieves a simple JavaScript web app that immediately takes the content of

the hash, uncompresses it, and displays it as text on the page.

For example:

Since my server never sees, much less provides, the content being displayed on the page, I posit that I should be immune to takedown notices. Even if I did receive one, what action could I take? I suppose I could stop hosting the app, but that hardly seems reasonable.

Say a website offered you a .doc file as well as a link to download Microsoft

Word so that you could view that file. If that file was found to contain

illegal or copyrighted material, we wouldn't say that Microsoft should stop

hosting Microsoft Word would we?

For the source code and more information, see the GitHub page.