100k skins: Reflections on the Winamp Skin Museum’s upload flow

When I launched the Winamp Skin Museum in 2020, we had 64k skins. Thanks to people’s generous use of the museum’s upload feature, on July 30th, 2024 we crossed 100k skins. I thought this would be a good opportunity to reflect on the design of the museum’s over-engineered upload feature, some of it’s clever tricks, and how its design and implementation have facilitated a virtuous positive feedback loop.

Goals #

The goal of the museum’s upload flow was to capitalize on the museum’s visibility, especially during the once-every-few-years moments when it receives massive traffic spikes from viral posts, to entice a small number of users with large collections to bulk upload skins which we are missing.

To achieve this goal, we must do a few things:

Make the process of uploading large collections easy (users are only so generous with their effort)

Make the process of uploading large collections fast (users are only so generous with their time)

Ensure we can scalably handle these large volumep uploads, even while the site is under heavy load

Achieve all of the above with a side-project budget

This is an interesting set of challenges because it forces us to deal with a difficult combination of challenges: Massive collections, processed easily and quickly, all with minimal resources.

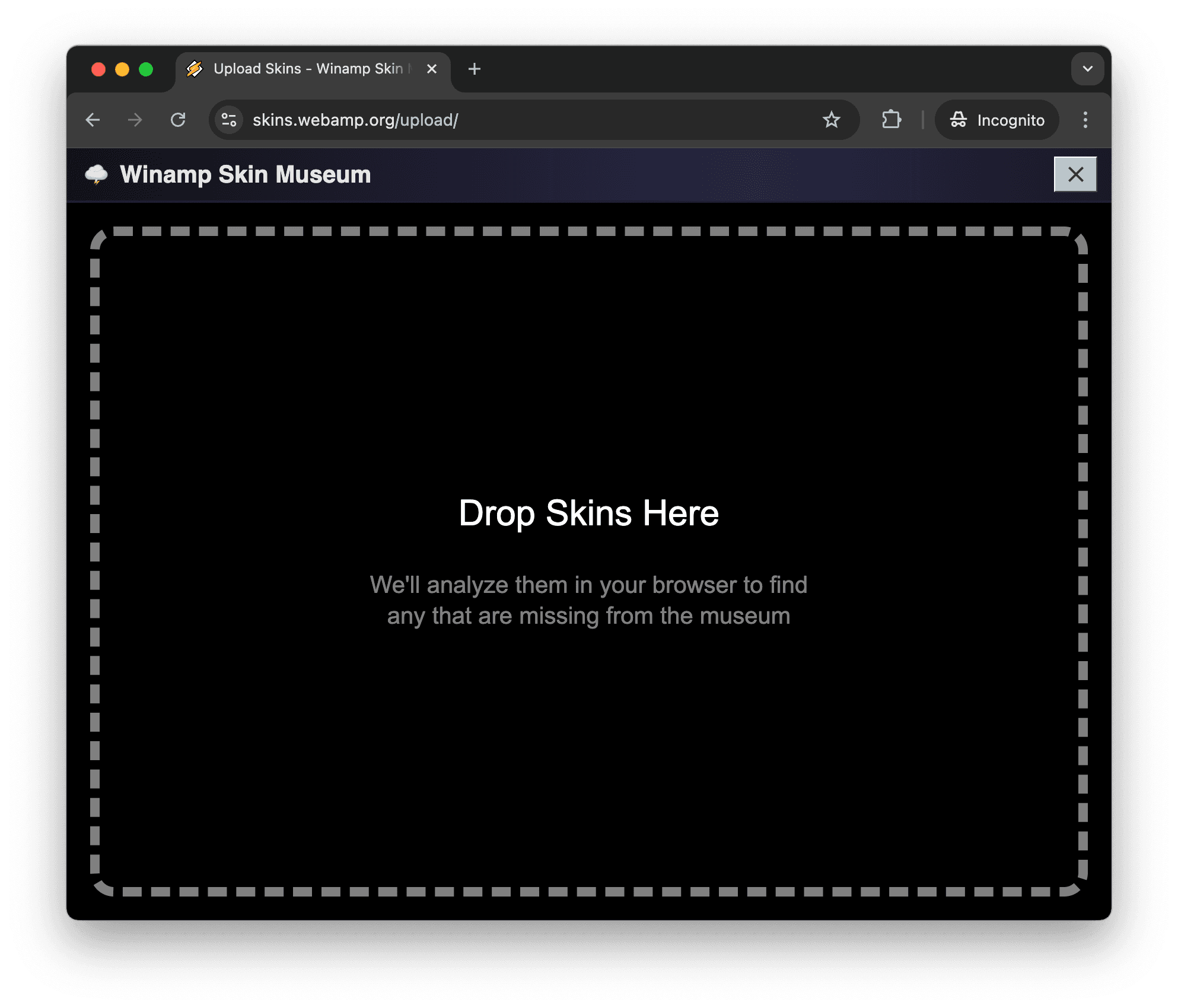

Make it easy #

To support users with large collections, we need to ensure that users can process their whole collection without needing to take an action for each skin. To enable this, the museum provides an upload flow where users can drag in whole directories, including nested directories. From there, the rest of the flow is automated. The user is shown which skins we would like them to upload and may click a single button to initiate that upload. As the upload progresses, they are given a progress bar for each, giving them a realtime overview of the progress and stage of each skin upload.

This is a stark departure from every other skin curation website, which generally featured an upload page where you could click to upload a single file, and then be asked to provide metadata about that file (name, descriptions, category, etc.) before clicking submit.

Make it fast #

Making the upload flow fast is enabled by a key observation: While the user’s own collection may be arbitrarily large, the number of skins they have which are missing from the museum, is likely much smaller. Even if a user has thousands of skins on their computer, probably only a few hundred will be new to the museum and thus they should only need to upload a few hundred files.

To take advantage of this, we have the user’s browser locally analyze the files that the they dragged in, and then check with the server to see which we are missing before we initiate uploads.

The code does the following:

Checks the file extension and file structure to ensure it’s a skin

Computes the md5 hash of the Winamp skin

The md5 hash is a short string that uniquely identifies the contents of a file. We send the server a list all the skins that the user has on their machine in the form of an array of md5 hashes. This allows the server to reply with a list of the subset of skins which we actually need them to upload.

Make it scale #

Handling a large number of concurrent file uploads could be challenging for the museum’s relatively wimpy server, especially if the server is already under high load from a traffic spike. As stated above, the upload feature’s availability and performance during traffic spikes, are critical. To address this requirement the upload flow leverages pre-signed AWS S3 URLs to allow the user’s browser to upload skins directly to S3. (I’m using “S3” in this article since it’s well known and was the original service I used. However at some point I migrated to R2, Cloudflare’s API compatible alternative to S3 which has free egress).

When the server receives a list of md5 hashes representing all the skins in the user’s collection, it replies with a pre-signed S3 URL for each skin that is currently missing in the museum. The user’s browser receives these URLs and begins uploading the skins directly to S3 in parallel. Once each skin is complete the client pings the museum’s server again to let it know the upload is complete. Since looking up md5 hashes in the database, and getting pre-signed URLs from AWS are both relatively efficient, the Museum can handle a nearly unbounded number of concurrent file uploads by taking advantage of the infinite scalability of AWS’s S3.

Make it affordable #

Once the skins are in S3, and the Museum’s server has been made aware of this fact, the critical work is done. The user can now safely lose interest and the museum will not lose out on any artifacts. However, before the skins are available for users to view we need to process the skin. This requires downloading the skin, unpacking it, extracting indexable text and taking a screenshot of it using webamp.org and Puppeteer, and uploading that screenshot to S3.

These are all relatively taxing on the server, especially if attempted in parallel. The museum manages this by maintaining a queue of skins which have been uploaded but not yet processed.

If the museum were a business, I might have opted to employ a serverless architecture which could scale horizontally to ensure skins get processed immediately even during upload spikes. But the museum is not a business, and instead must run as close to free as possible. To enable this, we simply allocate a single worker on the museum’s server to process skins. During a spike, the processing queue might get arbitrarily delayed, but it will always complete eventually, and never runs the risk of unexpectedly triggering an expensive AWS bill.

Reflections #

While we do get a small handful of skins uploaded every day or so, the majority of new skins have come from massive bulk uploads, usually correlated with a viral post about the museum somewhere.

In retrospect, this upload flow was designed, engineered, and built for just a handful of very special power users each performing just a single bulk upload. By building with these users in mind before they ever arrived, we’ve been able to capitalize on those fleeting moments when a viral post about the Museum attracted them, and they opted to contribute their personal collections.

I love how this has created a virtuous positive feedback loop. More skins attracts more attention, attracts more power users, resulting in even more skins and thus even more attention. The outcome of this feedback loop is that now over 100,000 (and counting) unique works of art are preserved and made accessible online for another generation to experience.